The Cinderloo Story

Who?

The Cinderloo Uprising was a relatively unknown early 19th century industrial dispute

centred around the small East Shropshire town of Dawley.

While the dispute started with only 500 miners a crowd of over 3,000 eventually massed on a pit mound located at Old Park.

Three Miners lost their lives as a direct result of the 1821 Cinderloo uprising they were;

Thomas Palin, was hanged on 7th April 1821.

William Bird, an 18 year old collier was killed outright.

Thomas Gittins (Ingle), was mortally wounded.

Others involved included Samuel Hayward (who was also initially condemned to death but later pardoned) while John Amies, Joseph Eccleshall, John Grainger, Christopher North, John Payne, Robert Wheeler and John Wilcox who were each jailed 9 months for riot.

The Shropshire Yeomonry representing the interests of the local Iron Masters numbered 70 armed men who were headed up by Colonel Cludde, They incurred minimal casualties.

Why?

Local Iron Masters including Thomas Botfield, the Lilleshall Co., John Anstice and John

Addenbrooke had made an illegal pact to reduce their workers wages by the not

inconsiderable amount of 6d per day! Following the uprising many local Ironmasters agreed to reduce the amount of the pay by the lesser amount of 4d a day.

While those achievements may seem modest, considering the loss of life. It is also fair to say that the true legacy of Cinderloo was its part in the ‘Class War’ catalyst which would

eventually cause a sea change in the UK political landscape. The most obvious results of this being the eventual legalisation of trade unions and the resulting improvements in

workers rights, pay and conditions.

Like the Peterloo Massacre, which took place two years earlier, in 1819, in Manchester, Cinderloo was so named in ironic reference to the Battle of Waterloo, which ended the Napoleonic War in 1815.

Where?

While much of Old Park has seen considerable change as a result of the creation of Telford New Town, there is a single remaining pit mound at the Cinderloo Uprising location which gives a great contextual setting to our story.

We will be producing maps to link the historical events and the routes that the miners took with the communities of Telford today.

Over Production…

By the early 19th century wages in the small Shropshire mining & foundry towns straddling the “Lightmoor Fault” had fallen into rapid decline..

..the ironmasters were finding it difficult to dispose of all their produce at a reasonable price. In 1821 this problem was still under discussion and Mr. Botfield of the Snedshill furnaces, as Chairman of the Shropshire Ironmasters, said: ‘They consider the present depressed state of the Iron Trade has been produced by the late increased make which has done serious injury to the trade in general and very little ultimate good to the parties. A reduction in the make is absolutely necessary and ought to take place.’ The principal problem for the Shropshire ironmasters was still the strong rivalry of the Welsh dealers in the Bristol market…The great iron works of Merthyr Tydfil, Cyfarthfa, Tredegar and others of the Welsh valleys, were now feeling their strength and increasing production at a great rate. (ref. 2)

While there ‘were signs of an improvement of trade towards the end of

1817…prices fell again in 1819.’ (ref. 3)

Discontent Brews…

The local Ironmasters and chartermasters decided to take matters in hand…

Employing methods that capitalists have continued to use until the present day, the great iron making dynasties of the east Shropshire coalfield endeavoured to make their workers pay for their crisis. They partook in an act of illegal combination and imposed a pay cut of 6d a day on the workers in the various concerns who laboured to produce their considerable wealth. This inevitably provoked a militant response from the colliers, who were already disaffected due to operation of the deeply unpopular – and again illegal – Truck System in the coalfield; and who had seen off a similar attempt to cut wages the previous year. (ref. 4)

Two days after the announcement that wages were to be reduced, the colliers went on strike. On 1st February, pits that were still working were visited by the strikers, who persuaded the employees to join the action. Following visits to ironworks at Ketley, New Hadley and Wombridge, production was brought to a halt by the plugging of boilers. (ref. 5)

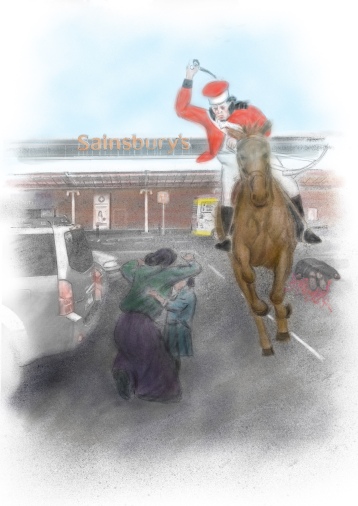

“About seventy men of Col. Cludde’s Yeomanry Cavalry having been assembled, we proceeded in search of the Rioters to the Iron Works at the Horse hay between this place [Wellington] and CoalbrookDale: upon our arrival there, we found that having effected their purpose and completely stopped those works they had proceeded to the works of Messrs. Botfield at the Old Park, to which place we immediately followed them.” (ref. 6)

The crowd of colliers was, by this time, around 3,000 strong. ‘Numbers of women and children had joined them on their route’ and they had gathered on and around the precipitous cinderhills that dominated the landscape surrounding the now idle ironworks. (ref. 7)

Violence Erupts…

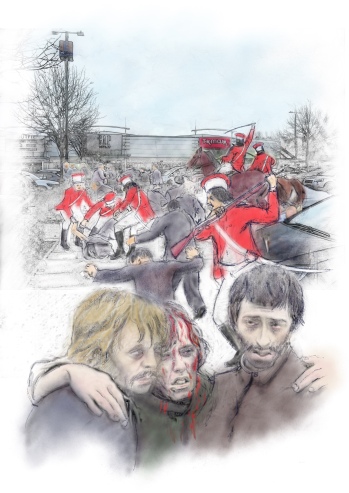

The hills were of great extent and composed of pieces of iron and iron stone, which had been thrown out from the pit mouths,& might have been accumulating for the last thirty years. There might have been a 100 tons of these pieces, of various sizes, some very large and heavy. The mob had taken possession of the tops of all the surrounding hills, were armed with sticks, and behaving in a riotous manner. (ref. 8)

Following the reading of the Riot Act by one of the magistrates, Thomas Eyton, which was met with many jeers and expressions of defiance, a period of one hour was allowed to elapse during which the ‘crowd remained very noisy and did not disperse.’ (ref. 5)

From his carriage, Cludde subsequently gave the order for ‘the cavalry to advance, to endeavour to disperse them doing as little injury as possible…and at the same time to assist the Peace Officers in taking into Custody any that were armed with bludgeons, or who appeared to be particularly active.’ (ref. 9)

‘ringleaders’ were arrested by the troops and put into the custody of John

Bayley, a constable of Malinslee. (ref. 10)

While the authorities were endeavouring to take these men to Wellington to await trial, the crowd of colliers amassed on the cinder hills adjacent to the road began to throw stones and heavy lumps of slag at the troops. Under the alleged leadership of a collier named Thomas Palin, a successful attempt was made to rescue the prisoners. In the ensuing panic the Yeomanry opened fire on the demonstrators. (ref. 9)

While the authorities were endeavouring to take these men to Wellington to await trial, the crowd of colliers amassed on the cinder hills adjacent to the road began to throw stones and heavy lumps of slag at the troops. Under the alleged leadership of a collier named Thomas Palin, a successful attempt was made to rescue the prisoners. In the ensuing panic the Yeomanry opened fire on the demonstrators. (ref. 9)

Deaths and Arrests…

A number of colliers and bystanders were wounded, including Thomas Palin, who received an incriminating shot wound to the arm that resulted in his arrest a few days later. (ref. 9)

William Bird, an eighteen-year-old collier from Coalpit Bank was killed outright, while Thomas Gittins, otherwise Ingle, also a collier, from Lawley Bank was mortally wounded. At the inquest into the men’s deaths on 6th February, the jury immediately returned verdicts of Justifiable Homicide. (ref. 1)

Many of the Yeomanry were said to have been badly wounded by the stones and slag showered upon them, but it appears the only serious injury was suffered by one hapless cavalryman, Mr. David Spencer, of Trench Lane, who was ‘dangerously, though accidentally wounded, in consequence of his pistol going off in the holster, which lodged the contents in his knee. (ref. 10)

Samuel Hayward was similarly sentenced to death, but was reprieved on 2nd April. (ref. 12)

Meanwhile Thomas Palin awaited his fate..

…in front of the County Gaol, in the presence of a large concourse of spectators. The behaviour of the unhappy man to the last moment was firm and becoming of his situation. Every exertion had been made…to obtain a commutation of his sentence, but without effect. (ref. 13)

Illustrations by Andrew Naylor

References:

1 A. C. B. Mercer, Jan 1966

2 A. Raistrick, 1989

3 Trinder, ibid.

4 I. Thomas 2004

5 Trinder, op. cit.

6 W. Cludde, et al, to H. O., 4th Feb 1821

7 Salopian Journal, 28th Mar 1821

8 Shrewsbury Chronicle, 30th Mar 1821

9 Cludde, et al, loc. cit.

10 Salopian Journal, loc. cit.

11 Salopian Journal, 7th Feb1821

12 Shrewsbury Chronicle, 30th Mar1821

13 Salopian Journal, 11th Apr 1821

See our Resources page for further detailed information about Cinderloo